about John Cage

PROGETTO DI EDIZIONE DISCOGRAFICA DELL'OPERA DI JOHN CAGE

a cura/curated by Sergio Armaroli

L'INTERVISTA

di Gabriele Moroni

La DaVinci ha avviato un progetto assai impegnativo dedicato all’opera di Cage. Di questo, e di una delle figure più ricche di influenza nella musica del XX secolo, abbiamo discusso con Sergio Armaroli, ideatore e figura leader nel progetto.

Maestro Armaroli, lei è poeta, artista, musicista, sembra esserci una comunanza di interessi fra lei e Cage. Da dove nasce il suo interesse verso questo compositore così controverso?

Io ho una formazione artistica che viene da arti visive e musica che ho cercato di fare convivere, e fin dagli anni di formazione Cage nel suo insieme (compositore, filosofo, poeta) mi è stato di grande aiuto ed ha accompagnato tutto il mio percorso artistico. Ho cominciato ad avvicinarmi a lui leggendo Silenzio edito da Feltrinelli, si era nei primi anni Settanta

Questi scritti, molto precisi quando Cage parla dell’uso dell’I-Ching o delle imperfezioni della carta come metodi cui affidare la scelta compositiva ultima, non sono poi così facili.

Cage ha questo aspetto pedagogico, volere spiegare e non spiegare allo stesso tempo: questa apertura, questo non esserci una risposta ma un continuo indagare e mettersi in gioco mi ha sempre colpito e cerco di trasmetterlo ai miei studenti.

Il rapporto con le arti visive è stato costante, già negli anni Cinquanta Cage ha avuto contatti con l’Espressionismo astratto, si incontrava spesso con Jackson Pollock.

Io ho studiato all’Accademia di Belle Arti, e devo dire che in questo ambiente Cage è stato capito da subito. Invece nel modo dell’ufficialità musicale ancora oggi è bensì riconosciuto come una delle figure fondamentali, però ancora con alcune riserve, perché mette in discussione postulati di base ritenuti inattaccabili nella musica in generale. Devo dire che Cage è molto conosciuto come filosofo ma pochi conoscono la sua opera, ed è per questo che con Edmondo Filippini e la DaVinci ho pensato di indagare proprio la sua opera di Cage dal punto di vista esclusivamente musicale, con la consapevolezza di questa complessità.

Come è nato questo progetto?

Ho studiato percussioni in Conservatorio a Milano e quando vi sono entrato il mio obiettivo era studiare approfonditamente la musica di Cage, che per un percussionista è come Bach per un organista. Cage fonda tutto il suo pensiero musicale dall’idea di una percussione ampliata, lo dice lui stesso. Ho studiato anche Musica elettronica cercando sempre di indagare parallelamente l’opera di Cage. Ad un certo punto ho sentito come l’esigenza di “ricambiare” il lavoro di molti anni proponendo una collana dedicata a Cage e costruita con musicisti che ho conosciuto durante il mio percorso e con cui ho stabilito un rapporto profondo, con loro ho registrato musica improvvisata.

Quanti CD sono previsti?

Per il momento 16. L’idea è di dedicare l’attenzione soprattutto a opere di Cage poco conosciute e con un approccio filologico, il che non vuol dire rispettare esattamente quello che è scritto sulla pagina: secondo me Cage richiede una consapevolezza maggiore, non lo si può suonare con un musicista che si conosce poco, ma con cui si ha una relazione musicale, di vita anche.

E gli interpreti quali sono?

L’Empty Words Percussion Ensemble, un gruppo che ho fondato insieme a Ben Omar: nei primi due CD abbiamo pensato di dedicarci alle prime composizioni di Cage per percussioni, Quartet e Trio, poco eseguite, e quindi alle ultime due, sempre per percussioni, Three2 e un Four4. Una delle poche certezze in Cage è che la percussione è il fondamento del suo pensiero. Francesca Gemmo, compositrice, pianista e compagna di vita, è stata coinvolta insieme a Giancarlo Schiaffini, con cui collaboro da molti anni nel jazz e nella contemporanea. Quindi Walter Prati, violoncellista che si dedica al live electronics e all’improvvisazione; Marco Fusi, con cui ho collaborato molto nella contemporanea. Francesca Gemmo ha inciso con Maria Isabella De Carli il Socrates di Satie trascritto da Cage per due pianoforti, mai uscito su disco, e Cheap Imitation per pianoforte. Con Steve Piccolo, che appartiene all’avanguardia rock fine anni Settanta, abbiamo realizzato Indeterminacy, una lunga lettura tratta dai diari di Cage, che verrà realizzata in due versioni, una improvvisata ed una “filologica”, che è quella di Cage con David Tudor. E poi c’è un giovane organista, Piergiovanni Domenighini, scelto al di fuori della cerchia di musicisti che hanno lavorato più volte insieme, per evitare il rischio di autoreferenzialità.

E pezzi famosi come quelli per pianoforte preparato o Music of changes?

Li abbiamo lasciati indietro perché vantano una ricca discografia. L’idea era quella di partire con una collana dedicata a Cage cercando però di concentrarci su alcuni pezzi poco eseguiti.

Questo spiega perché avete inciso diversi Number Pieces: One10, Two5, Two6, Three2, Four4…

Nei Number Pieces c’è un duplice motivo. La Mode Records negli anni Novanta aveva progettato di incidere la sua musica come Cage la pensava, perché tutti vedono Cage come un compositore estremamente libero ma in realtà era di un rigore assoluto, che si nasconde dietro l’ironia. La Mode Records ha voluto testimoniare questa importanza nel rigore che ha cambiato la chiave di lettura nella musica di Cage. Io dunque ho pensato di proporre un repertorio un po’ trascurato sotto questo punto di vista.

Mi ha molto colpito l’esecuzione di Four4, come avete concepito l’interpretazione? Nei Number Pieces Cage ha in genere indicato con precisione le altezze ma proposto delle “forchette” sui tempi, ad esempio, tra 0’00” e 0’45”.

Quando Fritz Hauser, il dedicatario di One4, chiese a Cage come eseguire il pezzo, Cage gli rispose La musica è tua e la devi suonare come sei. Cage dà una sorta di scheletro dentro il quale l’interprete può essere se stesso. Il suono è del musicista, la forma è di Cage, per lui la forma è il tempo. Con l’Ensemble il problema è più complesso, ma l’idea era quello di mantenere le proprie individualità, e i Number Pieces dovrebbero essere quasi delle improvvisazioni.

Ho trovato molto interessante questo brano per le sonorità…

Abbiamo usato diversi suoni però mascherandoli, senza impiegare la trasformazione elettronica.

C’è poi Renga… l’interprete si trova davanti schizzi che Thoreau aveva fatto sul suo diario e deve tradurli in musica…

Come lettura questo è un altro estremo di Cage. Abbiamo lavorato quasi un anno e mezzo su questo pezzo, lo abbiamo registrato più volte. Abbiamo fatto sovraincisioni perché Cage pensa a 78 strumenti.

Ma voi lo avete eseguito in 4…

Cage non si riferisce a 78 interpreti ma a suoni, lo possiamo dedurre da alcune sue lettere. Ci siamo divisi i suoni (io ad esempio ne avevo 35), e abbiamo fatto ricorso all’I-Ching per ottenere una serie di numeri che poi abbiamo collegato alla partitura, nella quale i numerini in alto indicano i singoli strumenti o suoni.

Quando è prevista la conclusione del progetto?

Non abbiamo una data certa, con Cage potrei rispondere A Year from Monday.

about CAGE | vol.1/2

A John Cage Compendium: Recordings (Last modified 3 January 2021)

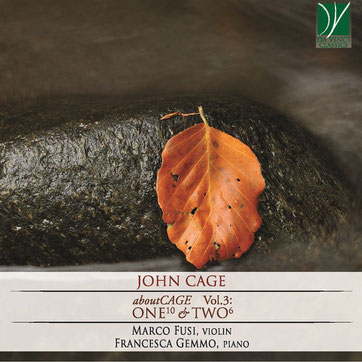

aboutCAGE | vol.3

John Cage: aboutCAGE Vol. 3: ONE10 & TWO6

John Cage: aboutCAGE Vol.3, ONE10 & TWO6

Marco Fusi, violin

Francesca Gemmo, piano

Artist(s): Francesca Gemmo, Marco Fusi

Composer: John Cage

EAN Code: 7.93611610569

Edition: Da Vinci Classics

Format: 1 Cd

Genre: Chamber

Instrumentation: Piano, Violin

Period: Contemporary

Quantity

ADD TO CART

Share

SKU: C00157

Category: Da Vinci Classics

ALBUM NOTES BY CHIARA BERTOGLIO

Imagine a music-lover turning the radio on. There is a programme of classical music. After a few seconds, the music-lover recognizes the fragment just heard as being a part of the Funeral March in Beethoven’s Eroica. The sequences of pitches, durations and timbre has acted upon the listener in a fashion similar to that of familiar features in a face we know. If listeners are also musically literate, they could even write down the notes they hear, and the result will be similar, if not equal, to the score seen by the orchestra conductor.

None of these experiences could apply to a broadcast of John Cage’s Number Pieces. The instructions given by the composer to the interpreters in the “score” can originate a number of performances whose aural features will be very different from one another; moreover, nobody who is not acquainted with the composer’s notation could “transcribe”, or derive, the original score by simply listening to one execution.

This is because the score of John Cage’s Number Pieces has a dramatically different concept than that of the Eroica, and purposefully so. This series of works, comprising between 40 and 48 pieces depending on the criteria adopted, was written by John Cage (1912-1992) in the final years of his life, starting in 1987. In Cage’s own words, “Another series without an underlying idea is the group that began with Two, continued with One, Five, Seven, Twenty‑three, 1O1, Four, Two2, One2, Three, Fourteen, and Seven2. For each of these works I look for something I haven't yet found. My favorite music is the music I haven't yet heard. I don't hear the music I write. I write in order to hear the music I haven't yet heard”.

While the label Number Pieces is not Cage’s, as it was created by James Pritchett, the titles of the individual pieces are interestingly fashioned. Each comprises a number written in full (such as One or Two) plus a superscript in digits. The first number indicates the quantity of performers involved, while the superscript identifies the order of composition: thus, One6 is the sixth piece written for one performer among the Number Pieces. As maintained by Robert Haskins, “Cage liked [these] titles because they were like the simple clothes he wore, the style of which never changed from day to day”.

If the quantity of musicians is clearly and neatly transmitted in the individual titles, the quality of the instruments played varies dramatically, and ranges from the most classical of the classical instruments (such as the violin and piano played in this Da Vinci CD) to the exotic sounds of the Japanese shō or of the rainsticks.

Nonetheless, the Number Pieces share also other common features; the first and foremost is their reliance on the so-called “time brackets”. In Cage’s scores for these works, the pitches are indicated rather traditionally, but the durations are prescribed by means of numbers specifying a temporal range within which the sounds can be initiated and/or terminated. These time brackets can be “fixed” (e.g.: this tone, or group of tones, should begin at 1’12’’ and finish at 2’35’’) or “flexible” (e.g. begin this tone at any time between 1’12’’ and 1’25’’). Cage’s time brackets are described by the composer himself in Composition in Retrospect (1981-88), one of his “mesostics”, i.e. verbal poetic forms in which words result from letters capitalized within the verse’s text. The words “VARIABLE STRUCTURE” are read in this mesostic about time-brackets:

it was part i thought of a moVement in composition / Away / fRom structure / Into process / Away / from an oBject having parts / into what you might caLl / wEather

now i_See / That / the time bRackets / took Us / baCk from / weaTher which had been reached to object / they made an earthqUake / pRoof music / so to spEak

[John Cage, Composition in Retrospect (Cambridge: Exact Change Books, 1993), 34–35.]

The definition of the time brackets’ pitch content was delegated by Cage to external forces. In the first Number Pieces, written between 1987 and 1989, the composer employed the I Ching, an ancient Chinese divination text, in order to determine certain compositional features; in the second period (1989-1992) this task was entrusted to a software, TBrack, developed by Andrew Culver, with whom the composer had already cooperated in the past. This choice was due primarily to Cage’s philosophy of composition, about which we will discuss shortly, but also to contingent reasons, such as the quantity of commissions he was receiving in his last years, and the consequent need to develop a compositional technique suited to these multiple demands.

The presence of flexible time-brackets (especially in works for more than one player) implies that the aural result of the pieces will be “variable” indeed from one performance to another. The overlapping of time-brackets produces what Cage described as “very complex eventualities, as what happens in life when you get involved in two things at the same time. One then has to choose whether to stop or continue…”. The implications of this for the performer are summarized by Glenn Freeman, an acclaimed interpreter of Cage: “This performance is only one realization. For almost all the number pieces, the notes will always be the same and in the same general order of appearance, no matter who realizes the work. The notes will fall at different times and have different durations, based on chance, but the piece is always the same length of time”. This variability was deliberately chosen by the composer: as Haskins points out, “At the end of his life, Cage wanted his music to be like writing on water—an act that left no traces”.

Cage’s choice was determined by his aesthetics, which increasingly favoured Far-Eastern philosophical approaches to time and creativity over the Western attitude which is more frequently found in “classical” music. Against the idea of “time-as-duration” which inspires the traditional notation of beats and rhythm, Cage wanted the feeling of “time-as-flowing” to pervade his works (as in McLuhan’s famous definition); ironically, however, this seeming freedom was pursued by the use of stop-watches for coordinating the various performers, thus creating a marked contradiction between the quest for a “natural” time and the means for obtaining it.

A similar contradiction arises in the treatment of pitches and elements of traditional harmony. While the “naturalness” of the Western tonal harmony was vehemently denied by Cage (who famously argued with his teacher Arnold Schönberg on these topics), undeniably some form of “harmony” is discernible in the Number Pieces (for instance, in those included in this CD). Cage himself was conscious of this, when he stated: “Harmony means that there are several sounds... being noticed at the same time. It’s quite impossible not to have harmony”. Thus, Cage’s works are a statement of intents against some of the most cherished values of the Western tonal music, such as the organization of time and harmony with a purposeful teleology, a narrativity, a consequential causality; these he countered with the Eastern principle of “interpenetration”, which he obtained through the use of overlapping time-brackets.

In consequence of this subversion of the traditional values of composition, also the relationships binding composer, work and performer(s) are transformed. As the preceding quote from Composition in Retrospect shows, Cage was more interested in the process of composition and performance than in the result, in the object produced; this is what makes the “facial features” of many of his works unrecognizable to the casual radio listener, and what allows certain aspects of his oeuvre to be described under the label of “open work”, as studied by the Italian philosopher and writer Umberto Eco. Against the idea that the composer’s genius makes the artwork, Cage famously maintained: “If you celebrate it, it's art, if you don't, it isn't”. Thus, Cage’s Number Pieces may be analysed only at a higher level than that of the pitches and durations studied by classical music theory; scholars such as Alexandre Popoff have employed statistical analysis and stochastic studies in order to highlight the “meta-structure” underlying these works, and the basic features which may be non-apparent when listening to them.

The two works performed in this CD both date from Cage’s last year, 1992, and were premiered posthumously. Two6, written in April, was performed in December by the two dedicatees, violinist Ami Flammer and pianist Martine Joste in Orléans, during a recital titled John Cage meets Erik Satie: the programme fascinatingly highlighted the relationship between the two composers, particularly by juxtaposing Satie’s Vexations with Two6, in which Vexations is used as part of the musical material. Fragments from the same work by Satie were also employed by Cage in Four3, thus linking two of the Number Pieces though their common reference to one of Cage’s favourite composers.

In turn, One10 for solo violin is strictly connected to another of the Number Pieces, One6: both were written for and performed by the violinist János Négyesy, in a fascinating event of multidisciplinary art. While Négyesy was playing, in fact, an ice sculpture by Mineko Grimmer was slowly melting, and the stones which had been frozen into it gradually fell into a pool, thus providing a visual and aural frame to the performance of the piece. In contrast with One6, which consists entirely of extremely long notes, sustained almost agonizingly by the violinist, One10 explores the use of harmonics. Once more, therefore, Cage explores the field between nature and technology: “time-as-flowing” against “time-as-duration”, the ambiguity about “harmony” and the “natural” origin of harmonics, the use of computer software and stopwatches, the liminal position between prescription and anarchy, the fascination for the void by a composer whose life was full of experiences and experiments. These contrasts should not be solved: they are, in fact, one of the most distinguishing features of Cage’s aesthetics and of his artistic output, and one of the aspects for which he will be remembered.

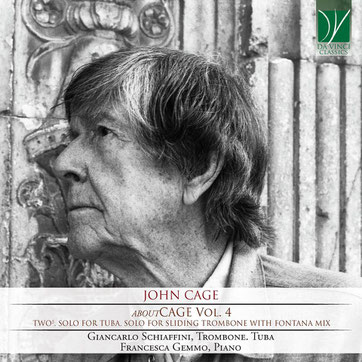

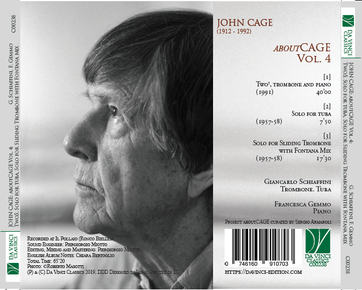

aboutCAGE | vol.4

John Cage: About Cage Vol. 4, Two5, Solo for tuba, Solo for Sliding Trombone with Fontana Mix

John Cage: aboutCAGE vol.4, Two5; Solo for Tuba

Solo for Sliding Trombone with Fontana Mix

Giancarlo Schiaffini, trombone, tuba

Francesca Gemmo, piano

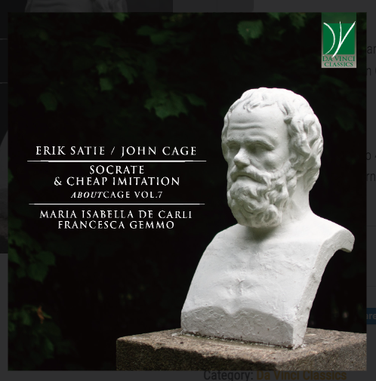

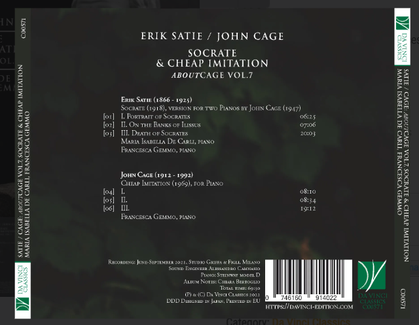

aboutCAGE | vol.7

John Cage: AboutCage Vol. 7 – Socrate (1947), Cheap Imitation (1969)

Artist(s): Maria Isabella De Carli, Francesca Gemmo

Composer(s): Erik Satie, John Cage

Edition: Da Vinci Classics

Format: 1 Cd

Genre: Chamber

Instrumentation: Piano, Piano 4 Hands

Period: Contemporary, Modern

Publication year: 2022

John Cage: AboutCage Vol. 7 - Socrate (1947), Cheap Imitation (1969) quantity

RECENSIONI | REVIEWS

Intorno a Cage. Sì, lui, ancora l’inafferrabile organizzatore di suoni per far vivere i suoni come sono, nella loro presenza nel mondo. Non serve la musica, diceva l’amabile sovversivo, anzi la musica è già una costrizione dei suoni. Poi li organizzava, altroché, chissà se era musica quella che scriveva. Probabilmente sì. Ancora intorno a John Cage perché è difficile trovarne altri così contemporanei. Sorprendenti, divertenti. Prendendolo in parola, un musicista che si sta rivelando protagonista della neo-neo-avanguardia artistica non solo in Italia, Sergio Armaroli, sostiene che con Cage finisce la musica e si apre la stagione degli spazi dove risuonano liberi i suoni. In questo cruciale momento di transizione Armaroli fa musica di improvvisazione, anima circoli di ricerca musicale e, da qualche anno, cura per le edizioni discografiche Da Vinci Classics una collana intitolata appunto Intorno a Cage (About Cage, per la verità). Esce ora il volume 7 della serie. Ci sono le due opere che Cage produsse in sintonia con Erik Satie, uno dei suoi idoli, forse il suo idolo in assoluto. In sintonia è poco: a suo dire Cage cercò di entrare nello spirito di Satie, di agire secondo la sua stessa logica musicale. Una delle due opere è la trascrizione per due pianoforti, fatta nel 1947, del Socrate dell’amato collega, cioè un lavoro per voce e orchestra nato tra il 1917 e il 1918 su testi di Platone. L’altra opera che si trova in questo volume 7, Cheap Imitation, è un pezzo del 1969 per pianoforte (ma arrivarono poi versioni per diversi organici, compresa l’orchestra) in tre movimenti, come nell’originario Socrate. Cage lo scrisse desiderando che fosse una ri-creazione del Socrate, un vitale fantasma che riappariva con altre vesti. Ovvio che entrambi i pezzi, anche la trascrizione, risultano assai cageani. Cheap Imitation fu registrata dallo stesso Cage «in un giorno di pioggia il 7 marzo 1976», come è riportato nell’album della Cramps uscito nel 1977. La versione della pianista Francesca Gemmo nel cd della Da Vinci è più vicina a… Satie che a Cage. C’è meno il tocco dell’avanguardia in chiave di scarna nudità del tracciato melodico e più un qualcosa di morbido, di delicatamente conversativo. La versione del Socrate di Satie-Cage è qui presentata dalla coppia di pianiste Francesca Gemmo-Maria Isabella De Carli. Si capisce dalla sapienza delle interpreti che Cage aveva cercato nella trascrizione di riprodurre non la vocazione «salottiera» di Satie ma gli esercizi di «impassibilità» che quell’autore amava. E allora si pensa alla «nuova oggettività» del Novecento, si pensa addirittura allo Stravinsky neoclassico. Quanti stimoli per la mente!

Mario Gamba

aboutCAGE | vol.9

- Artist(s): Sergio Armaroli, Francesca Gemmo, Fritz Hauser, Martina Brodbeck

- Composer(s): John Cage, Sergio Armaroli

- EAN Code: 7.46160917641

- Edition: Da Vinci Classics

- Format: 1 Cd

- Genre: Chamber

- Instrumentation: Cello, Drums, Percussion, Piano, Vibraphone

- Period: Contemporary

- Publication year: 2024

REVIEW | RECENSIONI et Commentaires

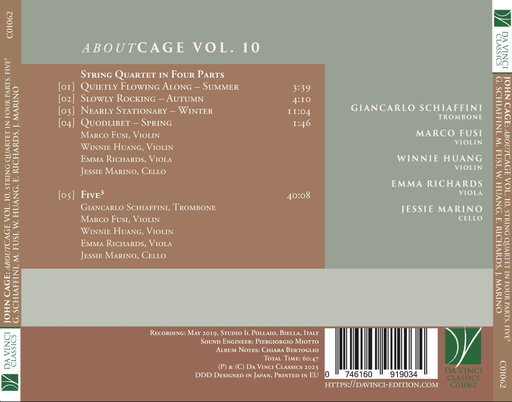

aboutCAGE | vol.10

Physical Release: 18 July 2025

Digital Release: 1 August 2025

- Artist(s): Giancarlo Schiaffini, Emma Richards, Jessie Marino, Marco Fusi, Winnie Huang

- Composer(s): John Cage

- Edition: Da Vinci Classics

- Format: 1 Cd

- Genre: Chamber

- Instrumentation: String Quartet, Trombone

- Period: Contemporary

- Publication year: 2025

Sergio Armaroli

Sergio Armaroli